The Federal Reserve’s Dual Mandate Dilemma

When the Federal Reserve members make public statements, global markets listen. The members can sway the world’s largest economy by controlling the availability and cost of money and credit. Therefore, their disagreement over the optimal monetary policy stance often provokes abnormal market volatility. In this bulletin, we explore the inception of monetarism in the U.S., explain the Fed’s Dual Mandate, pinpoint where the Fed targets currently stand and ask, how can we better read the Fed’s actions and statements to make hedging decisions? And should we?

Should Central Banks Intervene in Markets?

Whether governments need to intervene to achieve financial stability is a long-standing debate. In the 18th century, Adam Smith and the Classical economists suggested markets work best when given free rein because the price mechanism will act as an ‘invisible hand’ to regulate economies and create financial stability over the long term. The Keynesian School, following John Maynard Keynes in the early 20th century, disagreed. Keynesian economics argued for intervention through government expenditure (fiscal policy) to stimulate economic growth.

New Classical Economics and Monetarism both emerged in the 1970s in response to the failure of Keynesian economics to explain stagflation (high inflation, slow economic growth, persistently high unemployment). Their criticism forced Keynesians to rethink. Currently, the requisite level of government intervention is still debatable, but most economists now agree that achieving financial stability is impossible without government control over both fiscal and monetary policies.

The U.S. Federal Reserve

Whether governments need to intervene to achieve financial stability is a long-standing debate. In the 18th century, Adam Smith and the Classical economists suggested markets work best when given free rein because the price mechanism will act as an ‘invisible hand’ to regulate economies and create financial stability over the long term. The Keynesian School, following John Maynard Keynes in the early 20th century, disagreed. Keynesian economics argued for intervention through government expenditure (fiscal policy) to stimulate economic growth.

The FOMC is a 17-member committee that manages a dual mandate of maximizing employment and stabilizing prices (measured by the annual change in Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Index, not the Consumer Price Index (CPI)). The FOMC usually sets a 4% unemployment target and an annual inflation target of 2%. Sometimes, the FOMC allows inflation to tick higher than 2% in exchange for lower unemployment. Of course, the mandate is challenging given the two targets are negatively related (i.e., lower unemployment boosts purchasing power and pressures inflation higher). To achieve and maintain its targets, the FOMC intervenes in markets by either easing monetary policy (lowering the fed funds rate, expanding its asset purchase size, and lowering bank reserve requirements) or tightening it (doing the contrary).

The U.S. Economic Recovery Post COVID-19

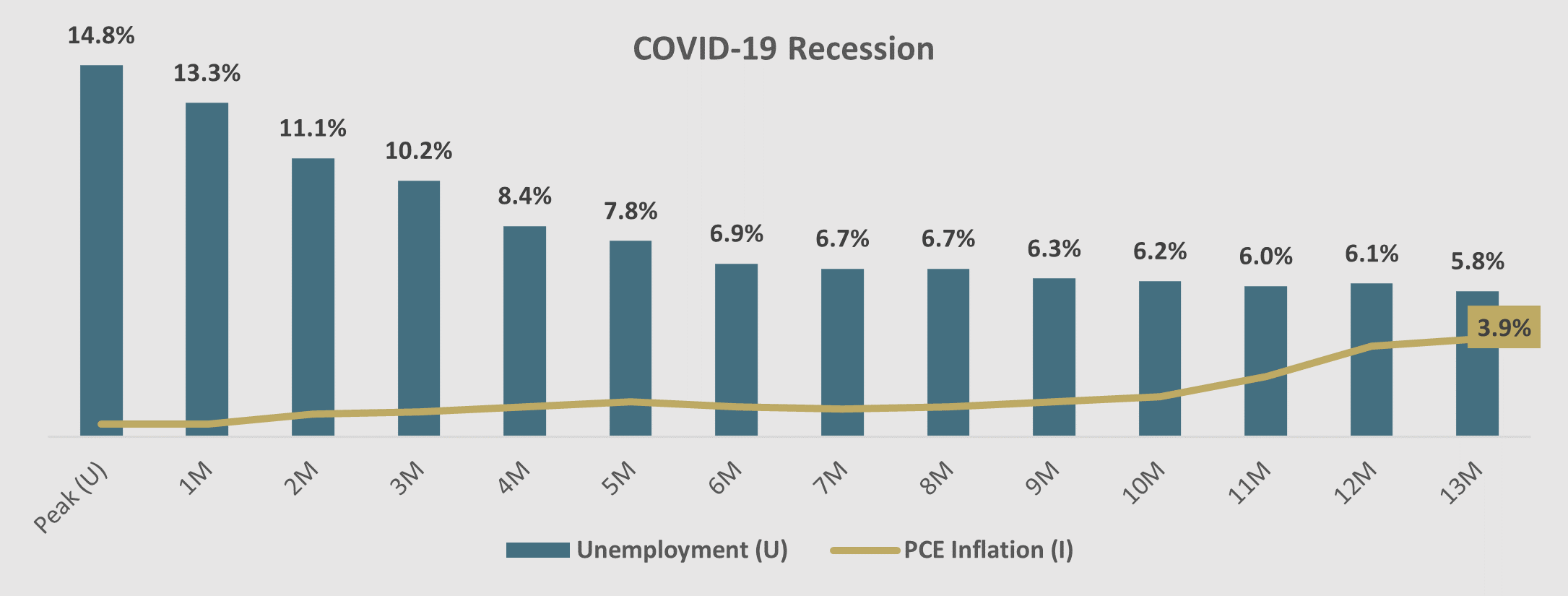

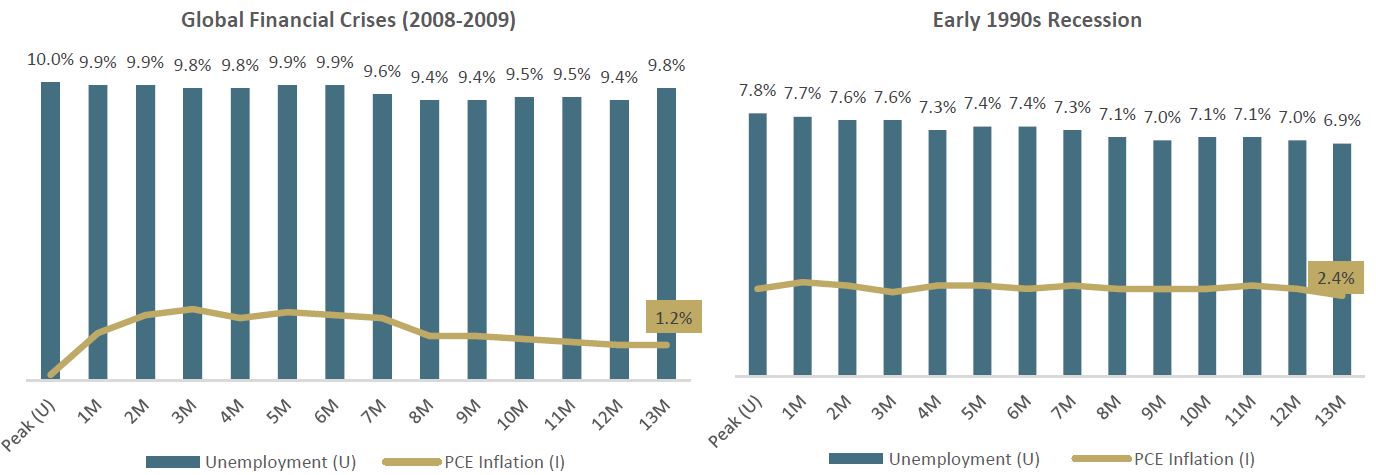

During the pandemic’s early days, forecasts on the shape of the economic recovery proliferated. Some estimated an expedited V-shaped recovery where the economy quickly overcame a hiccup in growth. Others forecasted a longer U-shaped recovery, while some anticipated an L-shaped recovery that entails several years before productivity returns to pre-pandemic levels. Most recently, economists predicted a K-shaped recovery, where some sectors recover while others continue to contract. Below is a comparison of the unemployment and PCE inflation levels in the 13 months following three recessions, starting from peak unemployment:

As the charts show, although unemployment remained short of the FOMC target, jobs growth after the COVID-19 pandemic was much faster than previous recessions. Nonetheless, the expedited recovery also pushed the PCE index further from the FOMC’s 2% target. Such a paradox challenges monetary policy decision-makers.

The FOMC Meeting

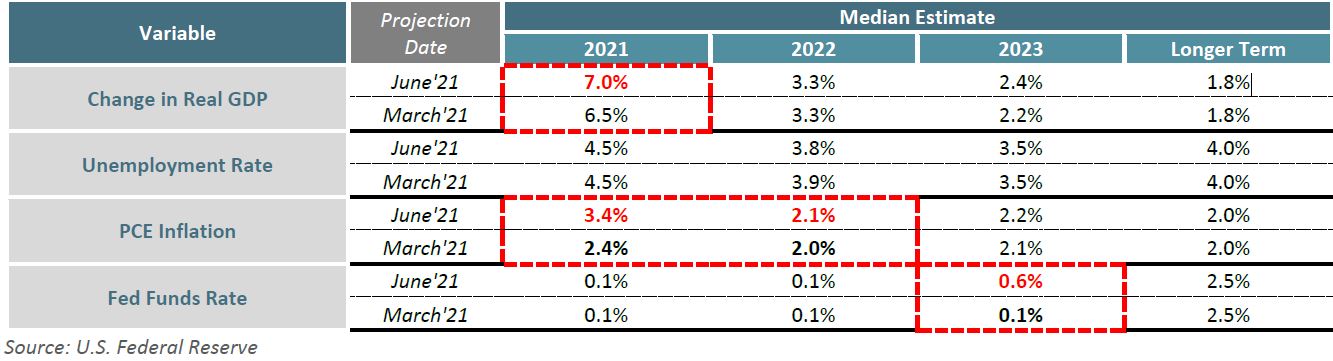

FOMC members hold eight regular meetings per year. Their purpose is to review and update the monetary policy stance and provide “Forward Guidance” on monetary policy depending on their estimate of the economic outlook. The last meeting was 15–16 June 2021. The members decided to keep their benchmark rate unchanged at a 0–0.25% range and the asset purchase program intact at $120 billion. But they updated their estimated fed funds rate to forecast at least two interest rate hikes in 2023. Market volatility tends to spike ahead of FOMC meetings, especially when both mandates are far from the target. Below is the Fed’s latest ‘median’ economic projection table:

As marked in the median projections above, the Fed now expects PCE inflation to reach 3.4% in 2021 then ease off by 2022. It upwardly revised GDP growth to 7.0% while projecting the fed fund rate at 0.6% in 2023.

How Could FOMC’s Projections Influence Risk Management Decisions?

FOMC projection readers must differentiate between what the FOMC can and cannot control. The FOMC controls monetary policy with the aim of influencing consumer behavior to achieve its target mandate levels. However, consumer behavior is a complex multivariable function. Despite the Fed’s accommodative policy, which theoretically encourages spending and discourages saving, deposits at U.S. banks continued to rise, reaching $17 trillion by May 2021. Therefore, it is also important to measure monetary policy’s impact on economic targets to better estimate the next Fed decision. In a presser following the last Fed meeting, Chairman Powell commented on the Dot Plot chart’s applicability, a chart denoting the members forward projection of Fed Funds Rate. Powell said, “The dots are not a great forecaster of future rate moves – because it’s so highly uncertain. There is no great forecaster – dots to be taken with a big grain of salt”.

There can be countless means to manage a corporate’s market risk exposure. However, they can be classified within three schools: conservative, dynamic, and opportunistic. While a conservative approach seeks maximum protection and accepts carrying the cost of hedging, an opportunistic approach aims to minimize hedging costs via timing the stage of an economic cycle. Nonetheless, all schools share the same objective of limiting exposure variability to tolerable levels. The closer to opportunistic an approach gets, the more resources it would require to forecast a market trend adequately.

We noticed that some local corporates try to take a shortcut to predict economic trends by relying on the forecasts of a reputable independent party, like the Fed. Nonetheless, relying solely on the Fed’s projections to make long-term corporate hedging decisions is a weak approach that will fail you in uncertain times. The Fed’s projections are dynamic and regularly updated, making them fragile forecasters over the long-term. The subjective element in risk management should always come second to risk limits protection, which is ideally done objectively. Once you achieve the desired risk limits protection, you can then subjectively rationalize expanding the hedge quantum. Still, subjective views should be clearly stated and should never exceed a pre-defined slice of an overall portfolio.