Comprehending the US Banking Crisis

Earlier this year, we observed the default of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a 40-year old commercial bank headquartered in California, United States. At the date of the default, 10th March 2023, this was observed to be the second biggest bank to have failed in the US history, following Washington Mutual which collapsed in 2008. SVB was closed and seized by the regulatory authorities, who cited the bank’s lack of liquidity and solvency for their action.

Days later, on 12th March 2023, another commercial banking institution, Signature Bank, was closed by officials in New York, where the institution was headquartered. A few months later on 01st May 2023, a third bank, First Republic Bank, also headquartered in California was foreclosed as part of what is now being termed the “2023 banking crisis”. First Republic Bank overtook SVB as the second largest bank to fail in the history of the United States.

All three of these banks were noted to have over USD 100 billion in assets at the time of their failure, with First Republic Bank and Silicon Valley Bank having assets over USD 200 billion in nominal terms. These events have led to US regulators and the Federal Reserve intensifying oversight across the banking system.

In addition, a renowned investment bank and financial institution, Credit Suisse, which is based out of Switzerland, also came close to a collapse and was reported to have struck a deal with the Swiss government in March 2023 to be acquired by another multinational investment bank, the UBS Group. This goes to show that the effects of economic uncertainty are not limited to only one geography or sector within the financial industry, but pose a systematic risk to the global financial system.

Economies globally have been tackling increased volatility in the financial system since the start of the COVID pandemic in 2020. The pandemic brought about a decline in economic activity, a blow to global supply chains and an effort by most nations to cut interest rates to zero or near zero to curtail the negative impact of the pandemic. Following that period, as the world began to move towards recovery, another shock came in the form of a conflict when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. This led to steeply rising commodity prices, particularly those of crude and food items. This caused decades of high inflation in most of the Western economies and what followed was the aggressive rate hiking that was undertaken to combat it.

Unfortunately, each time a problem is addressed, it mutates and branches out into a whole new set of obstacles, each of which necessitate the application of expertise and action to mediate. In this ever-evolving world of economics, it is important to learn the lessons from the past events, particularly those that took place in recent times. Good governance would entail understanding the risks that plague the global economy at the current times, and anticipating whether those risks can affect your business as well.

All institutions, not only those in banking, would benefit from studying the risks that brought about the crisis in these banks and fortifying themselves against the impact that these can have on their business and earnings by the application of sound governance and risk management principles.

The 2023 Banking Crisis

In general, a commercial bank operates by accepting deposits, primarily from individuals looking to earn interest on cash that they do not require for current expenditure, and issuing loans that can earn interest for the bank. Banks earn revenue by ensuring that the interest it gains from its loans is higher than the interest it pays to the depositors. In order to do this, the interest rate that bank’s charge on loans is usually higher to the rate that they offer to depositors.

Deposits are usually the largest portion of a bank’s liabilities, while the loans issued, and investments form the bank’s assets. Banks are commonly obligated to hold only a portion of liabilities, while the rest can be invested or used for lending. This portion is referred to as the Reserve Requirements Ratio and is established by the Central Banks and regulatory authorities.

Banks mostly prefer short-term loans/investments over long-term ones for a variety of reasons. First, long-term loans/interest rate securities carry a higher risk, both market and credit risk. In the case of market risk, a commonly used measure is the duration of the instrument, which is defined as the sensitivity of the price of the debt instrument to a change in underlying interest rates. In general, duration is higher for instruments with a longer tenor, which reflects the fact that the price of that instrument is more sensitive to a move in rates. Shorter maturity loans are also less susceptible to defaults as compared to those with a longer maturity.

Second, prudent banks aim to avoid an asset-liability mismatch, which occurs when the bank is obligated to settle short-term liabilities but holds more long-term assets. In such a case the tenor of assets and liabilities does not match and can lead to a collapse on account of insolvency (inability to sell-off the longer-term assets to settle debts), particularly in the case of an extreme event such as a bank run.

A run on the bank was indeed what led to the eventual collapse of SVB in early March. On the night prior, depositors abruptly asked for approximately USD 42 billion back. The cause for this sudden action is traced to apprehensions about SVB’s investment portfolio and an attempt by SVB to raise around USD 2.25 billion in new equity.

Unlike the crisis of 2008, which was brought about by multiple large banks investing in “toxic” assets (assets that were very unlikely to perform, including debt at a high risk of default), what occurred in the case of Silicon Valley Bank was quite different. The majority of SVB’s assets were its investments in US Treasuries and robust mortgage-backed securities.

However, as the Federal Reserve continued its fight against inflation, by conducting consecutive rate hikes aimed at bringing down inflation to the Fed’s 2.0% target, the side effects of the policy also began to manifest. Starting in March 2022, the Fed has carried out 10 rate hikes, which included 4 straight 75 basis point increases. As the underlying rate increases, the value of the bond decreases. The Fed moved fast and raised rates in quick succession, and as a result, the market value of SVB’s Treasury and Bond holdings declined rapidly.

While SVB could simply wait out the term of their securities with a long tenor to not realize the losses due to the decline in value, the Mark-to-Market of these instruments declined starkly as well, leading the bank towards insolvency. As noted earlier, interest rate instruments with a longer tenor are greatly sensitive to movements in underlying rates and the fact that the majority of SVB’s investment portfolio was made up of these aggravated the problem.

Some reports stated that SVB attempted to prevent insolvency by selling off some assets and raising the amount. However, this was not to be, as these attempts sparked panic among the market that led to the bank run that finally sealed Silicon Valley Bank’s fate.

The New York based Signature Bank failed and was shut down by regulators merely days after the collapse of SVB as the apprehensions around insolvency led to a bank run on it. However, reports also noted that Signature Banks faced significant liquidity risk on account of a low cash reserves and huge losses stemming from its cryptocurrency investments. First Republic bank, a California based bank larger than SVB, also closed its doors permanently in May pointing to a systemic risk within the US financial industry. Management at First Republic later attributed its collapse on what happened with SVB and Signature bank, while also describing the decreased earnings from steeply rising interest rates as temporary.

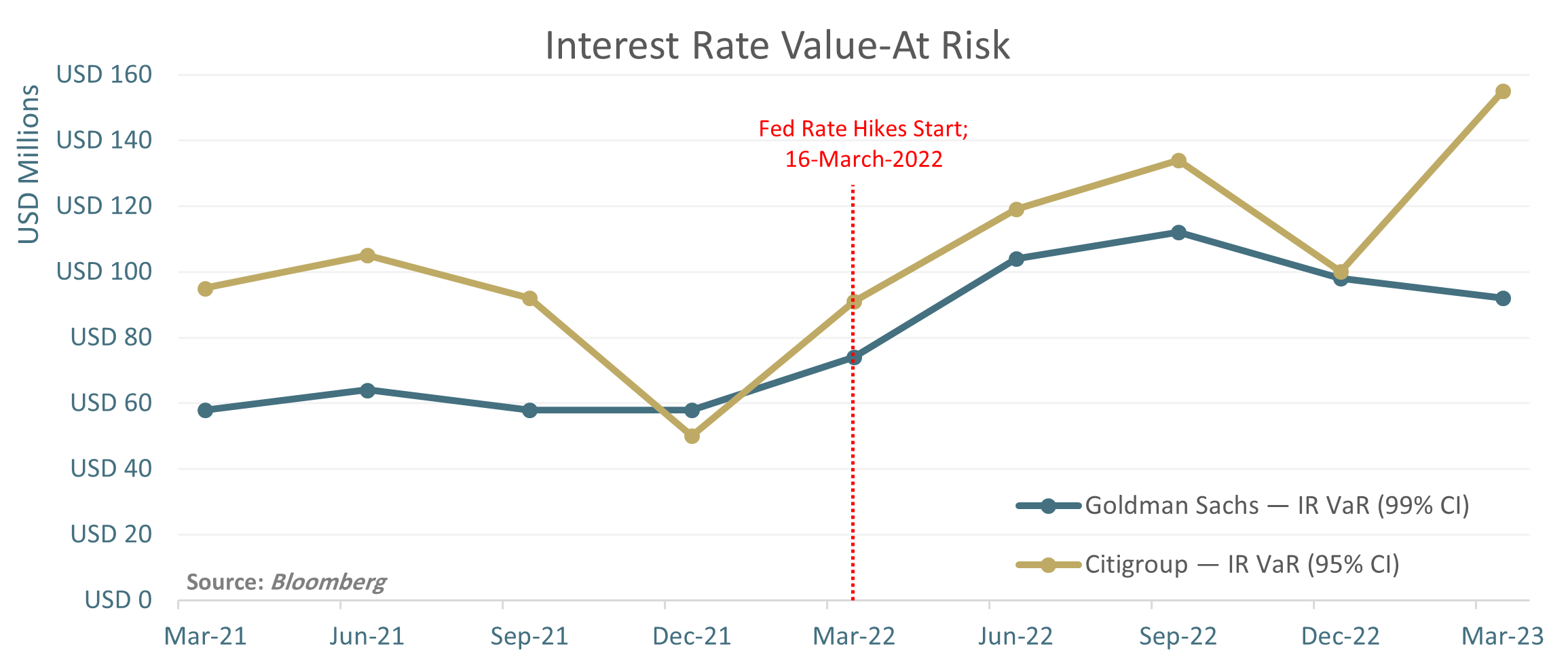

Most banking and financial institutions have risk management procedures to quantify the impact of unfavorable movements in the markets to their portfolio. One of the commonly used measures is the Value-At-Risk (VaR) which is calculated by these institutions as part of the risk management framework. The VaR measure is used to compute the amount of loss a firm may incur within a certain time span and with a given level of probability. As an example, a 1Y 95% VaR of USD 1 million can be interpreted as there being a 95% Confidence in the loss not exceeding USD 1 million within the next 1 year, with there being a 5% probability of a loss greater than that amount in the same period. Some of the larger financial institutions report their Value-At-Risk calculations on a periodic basis, giving an insight into the risk associated with their portfolio.

The chart above demonstrates the quarterly Interest Rate Value-At-Risk reported by two eminent US banks – Goldman Sachs and Citigroup. This is the VaR calculated on their interest rate investment portfolio. It can be observed that the IR VaR rises steeply for both following the initiation of the Federal Reserve’s rate hike campaign. Similar results can be observed across other financial institutions as well. The VaR metric is also frequently employed by firms outside of the financial industry as they aim to measure the impact of rising rates to their holdings and financing charges, and eventually employ mechanisms to counter the uncertainty.

Key takeaways

The recent crisis demonstrates the significant uncertainty in the global markets and the severe impact the occurrence of these risks can have on an institution. However, they also provide an opportunity to understand the sources of these risks so that firms can take action and employ mechanisms to counter them. This can be extrapolated to corporates outside the financial industry as well, while following the same principle.

The first key lesson presented here is the importance of a framework that outlines the procedures for managing risk, using both on-balance sheet and off-balance sheet approaches. The primary step in this process is to identify the sources of risk and quantify their impact to the firm’s KPIs (like earnings, ROE, etc.). This can be achieved by using statistical techniques such as the VaR metric described earlier. The risk to the KPI can then be mitigated either by using financial instruments like swaps (Off-Balance Sheet approach), or by examining the firm’s current interest rate assets and cash to establish a hedge (On-Balance Sheet approach).

The second takeaway from the recent events is the importance of aligning the firm’s assets and liabilities to ensure a capital structure that can promote the growth and earning objectives, while also ensuring that sufficient liquidity is maintained. This mechanism is sometimes referred to as “Balance Sheet Optimization”, and is required to ensure working capital adequacy and reviewing the sources of risk to the P&L. As examined earlier, it is important to examine the exposures from the assets and liabilities, and the duration of these exposures. Holding illiquid or longer duration assets can subject a firm to higher risk and may cause disruptions in the fulfillment of financial obligations.